Physiotherapists are the health professionals on the job when it comes to advocating the public to lead physically active lifestyles. Our occupation is fortunate to have longer contact time at a face to face level with people of a wide range of health statuses and conditions. The nature of our profession requires that we find out about the physical demands in a client / patients life, tuning into behaviour change talk, and empowering these persons to leave our care more enabled to participate in physical activity / exercise or empowered to make positive health decisions. When it comes to prescribing exercise the physiotherapist is looking to advocate long term engagement and adoption of these health behaviours. What better way of doing this, than to tell them to enjoy it! Let me explain.

Physios do a great job empowering patients to manage pain, whether it be education about the mechanisms causing pain or strategies to reduce the level of pain whilst promoting movement. When it comes to exercise education and monitoring, we do a lot of things well, like teaching activity pacing for those acutely unwell or supervising exercise of deconditioned persons in the acute care environment. There are some things we don't do as well. Prescribing moderate intensity exercise (particularly continuous exercise like fast paced walking, biking, rowing, swimming.... or burpies) is one of these things. From your own experiences you will be aware that when the cardiovascular envelope is pushed, much like pain, it can be uncomfortable.You won't be surprised to learn that the same experience is true for the client / patient.

Typically we ask clients to use a visual rating scale or a numerical rating scale, we simply insert the factor we want to measure "on a scale of 0 to 10 where zero is no ___ and ten is ____..." When it comes to exercise prescription, we either advocate for mild to moderate intensity, a 4 - 6 out of 10 on the scale. Great, they can talk but we don't have to listen to them sing! We know the intensity will achieve a wide range of health outcomes if the duration and frequency of other activities are accumulated to be greater than 150min throughout the week (ACSM guidelines). We would expect the energy systems of the individuals exercising at these intensities are tipping toward the predominant use of the anaerobic energy system. Give the exerciser a few minutes and they will find the physical activity is becoming pretty hard work. There are a number of reasons that this may be the case: deconditioning / poor exercise tolerance, mismatch of perceived 'fitness' and the task, initially over-exerting themselves, poor body awareness, inefficient movement patterns, poor understanding of the rating scales... maybe it's just unsustainable hard work and cognitively or emotionally, the activity is just not pleasurable.

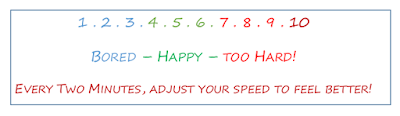

As a practitioner we can entertain the idea of having the patient enjoy the exercise by throwing them a numerical rating scale, asking them to feel good whilst exercising. Feeling good whilst exercising, only to feel good having exercised sounds like an upward spiral that would promote exercise and healthy lifestyles! Let me introduce a tool that can help us all achieve this!

The Feeling Scale

The feeling scale is a means of mindfulness. The physiotherapist usually aims to achieve a set exercise prescription (e.g. 10min exercycle session, HR 40-60% HHR) however this approach has a change of perspective; it has a process orientation focus rather than an outcome orientation focus. It encourages reflection in action, appraising the enjoyment of the exercise whilst exercising. Intensity is the key variable that can be changed whilst exercising (although not exclusive; you will see that the mode of exercise could be interchanged to achieve a longer duration of exercise too).

The Feeling Scale (Hardy & Rejeski, 1989) actually looks like this (below).

- +5 Very Good

- +4

- +3 Good

- +2

- +1 Fairly Good

- 0

- -1 Fairly Bad

- -2

- -3 Bad

- -4

- -5 Very Bad

Hardy, C. J. & Rejeski, W. J. (1989). Not what, buy how one feels: the measurement of affect during exercise. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 11(3), 304-317. DOI: 10.1123/jsep.11.3.304

It's a promising tool that deserves greater recognition by health professionals, namely physiotherapists. It is recognised that individuals who use the feeling scale will exercise at a sufficient intensity to elicit health gains (1, 2) with exercisers usually achieving the ACSM guidelines for exercise intensity. The clinician will ask the client to exercise at an intensity that makes them feel good (+3) and have the exerciser evaluate how they feel every 2-5 minutes. If the exerciser rates their affective state below (for example) +1 fairly good, then the clinician should ask the exerciser to adjust their own intensity to improve their rating on the feeling scale.

The peak and end rule simply predicts that the person exercising will remember the peak affect during exercise and the peak affect post exercise. The important thing to note here is that self-selected exercise intensity tended to have higher peaks on the feeling scale when compared to prescribed exercise intensity (3). What does this mean for physiotherapists? The exerciser will be more inclined to remember the peak and end affect of their exercise, so if the physio can make it an enjoyable experience then the exerciser is more likely to engage in that activity in the future.

There is a lot of research going on in the exercise psychology field which needs a bit more publicity in the physiotherapy community.

The peak and end rule simply predicts that the person exercising will remember the peak affect during exercise and the peak affect post exercise. The important thing to note here is that self-selected exercise intensity tended to have higher peaks on the feeling scale when compared to prescribed exercise intensity (3). What does this mean for physiotherapists? The exerciser will be more inclined to remember the peak and end affect of their exercise, so if the physio can make it an enjoyable experience then the exerciser is more likely to engage in that activity in the future.

There is a lot of research going on in the exercise psychology field which needs a bit more publicity in the physiotherapy community.

References

- Hargreaves, E. & Parfitt, G. (2008). Can the feeling scale be used to regulate exercise intensity. Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise. 40(10), 1852-1860

- Hamlyn-Williams, C., Tempest, G., Coombs, S. & Parfitt, G. (2015). Can previously sedentary females use the feeling scale to regulate exercise intensity in a gym environment? An observational study. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation, 7(30), DOI 10.1186/s13102-015-0023-8

- Parfitt, G. & Hughes, S. (2009). The exercise intensity - affect relationship: evidence and implications for exercise behaviour. Journal of Exercise Science and Fitness 7(2), S34-S41.